America’s Sweetheart Mary Pickford, one of the first global movie stars, wrote a letter to Paramount co-founder Adolph Zukor in 1925 asking for help preserving one of her films. Celluloid was dangerously flammable, which is why most silent films are now lost. With the help of Universal Founder Carl Laemmle, a print of Pickford’s Stella Maris (1918) was copied and stored safely for posterity. “As you know, it is my favorite picture – the only one I am sincerely proud of – the thought of its being destroyed actually hurt me,” Pickford wrote, “I felt [if the film were lost] as if someone near and dear to me were being injured.” Even though movies were barely a quarter century old, Pickford felt that motion pictures “have always been living, breathing beings to me.” A sentiment generations ahead of her time.

The movie-mad history of Los Angeles is alive all over the city. Anyone who has stepped onto a studio lot can feel the weight of the past as if the energy radiates from every building. The latest news pulling at the heartstrings of Hollywood history lovers is on the Warner Bros. lot where the famed Termite Terrace, a formative home of the Looney Tunes, is about to be demolished. These buildings are where Jack Warner, notoriously ignorant of his company’s animated characters, asked legendary animator Chuck Jones “how’s our mouse doing?” Despite Warner’s complacency, he kept the unit open for all those years, and it became one of the most important animation operations in history despite its location in the back corner (like the department’s first location at the Bronson studios in the 1920s).

Just last week, I was on the Warner Bros. lot to deliver a Lunch & Learn event for the tour guides and other staff interested in what I uncovered in my latest book, The Warner Brothers (2023). The morning before my event, I took the studio tour. One of the kids on our tram said he was a fan of the Looney Tunes. It broke my heart knowing that the building that birthed adventures for Bugs, Elmer, Daffy, and company was facing the backhoe. Termite Terrace, as it was known, should be part of the tour, without question. Fortunately for the rest of us, the fabulously animated tour guide, Scott Sala, was prepared with engaging Warner lot history from television like Friends, Gilmore Girls, and Pretty Little Liars to locations for Gremlins (1984), Rebel Without a Cause (1955), The Shootist (1976), and Strangers on a Train (1951). When I told Scott I was on the lot to discuss Warner history, his eyes lit up. Out came stories about where Jimmy Cagney dodged bullets in The Public Enemy (1931), where Humphrey Bogart walked into a bookstore in The Big Sleep (1946), and where Lana Turner strutted her debut in They Won’t Forget (1937).

For a studio tour like the one at Warner Bros., their history is part of the business model. Selling the iconic past to fans and curiosity seekers creates excitement for what is in store for the future. My lunch with the tour guides proves my case. Not only were they full of knowledge about Warner Bros., but they were also thirsty for more. We had a delightful discussion, ranging from how the brothers ended up in Burbank, to how they led the charge against Nazism in Hollywood, and how they always saw their studio’s purpose as serving a greater calling.

Noteworthy movie history is everywhere in Los Angeles. A trip down La Brea Ave can elicit both the silent comedy world of Charlie Chaplin as well as the creative genius of Jim Henson – and that’s just one single building. The Bronson studio on Sunset, now the home of Netflix, was where Warner Bros. first incorporated in 1923. The Lasky-DeMille barn, now the Hollywood Heritage Museum, has been moved from its original location to preserve the structure. It now sits across the street from the Hollywood Bowl – itself and important piece of Hollywood history. Anyone who’s been fortunate enough to walk through the original gate at Paramount Studios can do so while imagining Gloria Swanson being chauffeured on the lot in Sunset Boulevard (1950). People regularly pay their respects to Tinseltown’s past at the Hollywood Forever cemetery. The Thalberg building still sits on the Sony lot. Amazon owns the Culver studios.

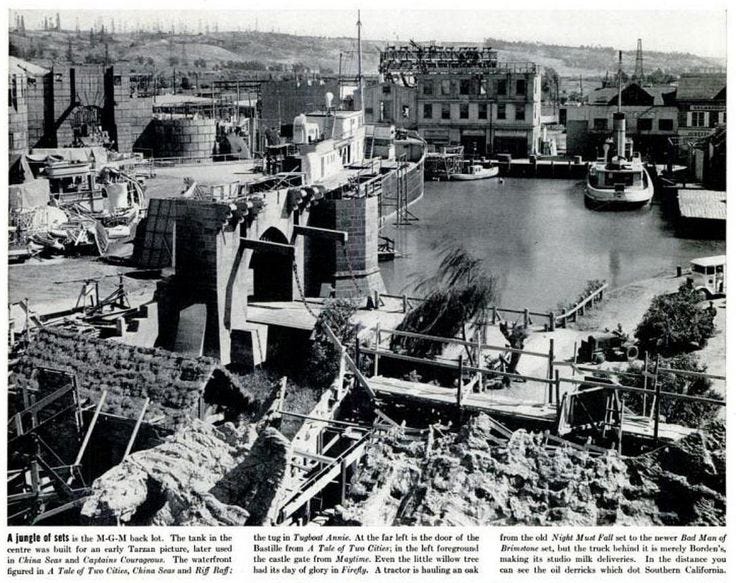

We all know the painful fate of the MGM lot, once the largest studio in Hollywood. The lot was mile long from administration across stages and sets, the studio was purchased by Kirk Kerkorian in 1969, who then stripped the studio and sold it for parts. As buildings were demolished and priceless props were tossed in the trash, Debbie Reynolds worked tirelessly to save as much as she could. More recently, others worked to save Marilyn Monroe’s house from the wrecking ball. Less fortunate was the storied Beverly Hills estate once lived in by Charles Boyer, Howard Hughes, and Kathryn Hepburn, which was demolished so NBA star Lebron James could erect a modern monstrosity.

Selling Hollywood’s history is good for business because it exposes the foundation of today’s entertainment industry. Every production stands on the shoulders of the industry’s fearless founders who laid the groundwork for modern entertainment. It’s what brings people to Los Angeles, a city that has been a hub of entertainment and progress for over a century. The Hollywood Sign, a land advertisement turned timeless icon, is one of the most recognizable monuments on the planet. The original Hollywood Realty Co responsible for the Hollywood sign still stands across from archways welcoming us to the canyon.

The stories that made Hollywood bring both local and tourist traffic to locations across the city, into restaurants like Musso and Frank’s, across the street to bookstores like Larry Edmunds, down Sunset to Book Soup, and over to Los Feliz for Skylight Books, onto the studio lots, into the hotels, to events like the Turner Classic Movie Festival, institutions like the new Motion Picture Academy Museum, flea markets like Melrose Trading Post, and so on. Those who took the Warner Bros. Studio Tour may head across the street for a meal at the Smoke House. The ripple effects of people trafficking the important history of Hollywood will only continue if relics of that story survive.

Hollywood’s story is part of American mythology. For over a century, Los Angeles movie studios have made stories that put us into relationship with the world. Losing an important building that has housed globally adored productions feels like someone excavating a corner of Gettysburg to put up a big box store. Instead, studios should put many buildings on the National Registry of Historic Places, a process that awards lucrative tax credits for restoration and will ensure future tourists and Angelinos can enjoy part of the history that made Los Angeles a destination that never stops attracting attention.

The day after we visited Warner Bros., my wife and I had dinner at the famous Formosa Café. As we sat on the Pacific Electric dining car attached to the restaurant, we could look across the street at one of the original United Artists buildings. Sitting in a historic train car like those that brought people west at the turn of the twentieth century, and in where so many stars and movie people dined, while staring across the street where early Hollywood history was made, is a sublime experience that allows us to be simultaneously in the past and present. It is the celebrated past the made the present possible. These buildings, like the films Miss Pickford sought to preserve, are living and breathing pieces of history always in need of guardians.