It Can Happen Here

On the relevancy of Nuremberg (2025) and Douglas Kelley's Timeless Warning

Brownshirts are storming US cities, murdering US citizens, while Trump administration supporters yell “comply or die” from the digital rooftops. People are disappearing, some criminals, others asylum seekers, and even more non-violent undocumented immigrants. Each of them guaranteed due-process by the 14th amendment of the US Constitution. We’ve often asked if fascism could take over the US and we’ve routinely felt that America is simply better and stronger than other countries where it’s happened before. That arrogance is fading fast. The reliably even-handed Jonathan Rauch has written in The Atlantic this week about Trump in simple terms: “yes, it’s fascism.”

Today is Holocaust Remembrance Day, yet not enough media outlets are making substantial note. Recent months have found reference to the Nuremberg Trials with many suggesting that a similar domestic tribunal will be in order following the past year’s reckless ICE activity in the United States. An interview with Gen-Z republicans by City Journal showed respect for Hitler and animosity for Jews.

The new film Nuremberg (2025), which was criminally shut out of the Oscars, is worth noting for bringing history to life in the present. Nuremberg focuses on the psychological struggle between U.S. Army psychiatrist Dr. Douglas Kelley (Rami Malek) and imprisoned Nazi leader Hermann Goring (Russell Crow) after World War II. Assigned to determine whether Nazi officials are mentally fit to stand trial, Kelley finds himself drawn into a tense battle of wills with Goring, who uses charm, intimidation, and intellect to manipulate those around him.

The film argues that Goring and the other defendants are not insane monsters but rational men who knowingly chose evil, a realization that deeply unsettles Kelley and shapes the prosecution’s strategy at the Nuremberg Trials. Rather than emphasizing courtroom spectacle, the film centers on the disturbing idea that ordinary human psychology can coexist with extraordinary cruelty, leaving Kelley emotionally scarred by what he uncovers.

Based on Jack El-Hai’s 2014 book The Nazi and the Psychiatrist, Nuremberg is captivating and its history still very much alive in the present. Like any great work of historical adaptation, the film gives us enough to spark curiosity to learn more. Dramatic films about history often have to invent dialogue and condense the timeline, all part of artistic license. After watching Nuremberg, I wanted to know more about Douglas Kelley and his work, which wasn’t well received because he was showing how the rise of fascism could happen anywhere…even here.

The rising popularity of authoritarianism and fascism in the US and around the globe has sparked renewed interest in movies about Nazi Germany. Films like The Zone of Interest (2023) offer a glimpse into the life’s of those who stood by and “let it happen” while a film like Civil War (2024) provides and uncomfortably prescient take on what our future could look like.

The dialogue in Nuremberg feels very present because films are always informed by the surroundings of their creation. “He made us feel German again,” Goring told Kelley, “we can reclaim our former glory.” The story is ripe with contemporary parallels and the film ends with a prescient quote form historian RG Collingwood: “history is for human self-knowledge. The only clue to what man can do is what man has done.”

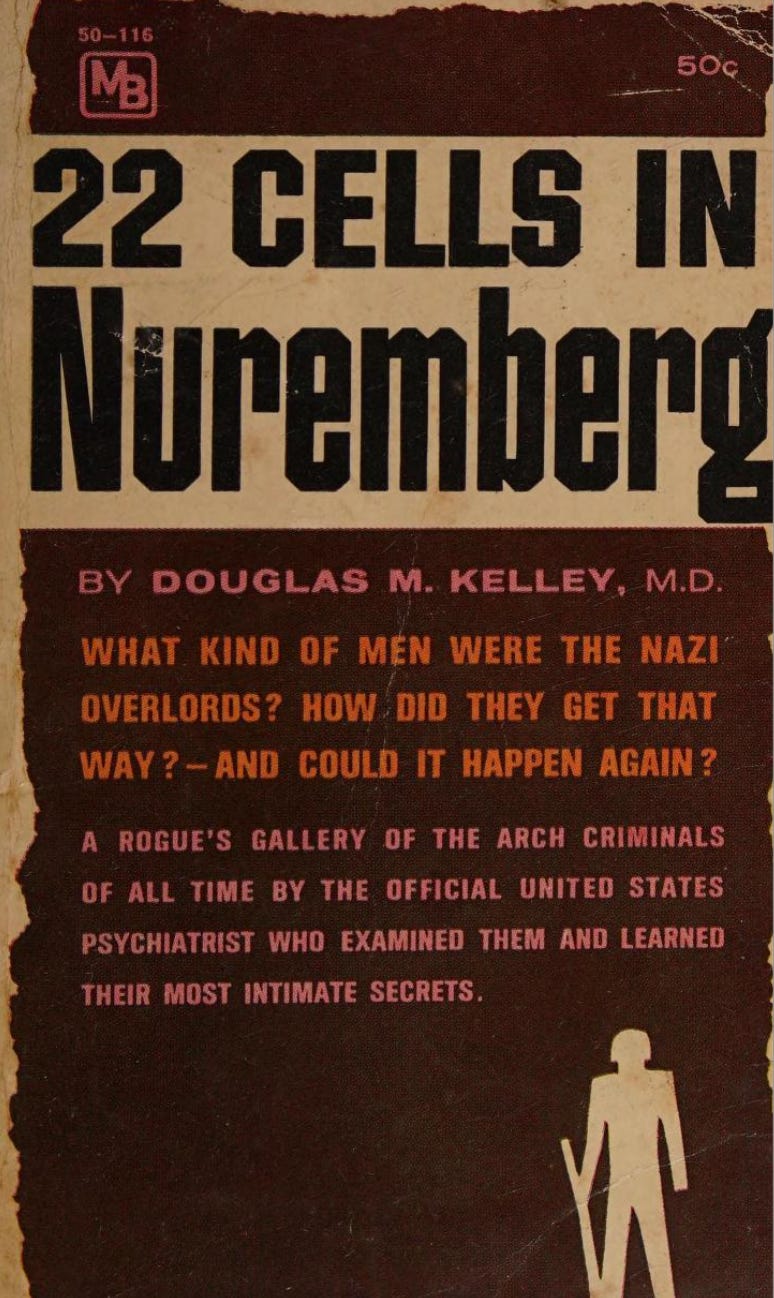

After the trial, Kelley penned a book titled 22 Cells in Nuremberg. It was poorly received because it offered a sobering reminder that the US is, in fact, was no better than Germany. Kelley simply argued that it can happen here.

Most damning is the concluding chapter that focuses solely on what his findings mean for the United States. “This [Nazi] political machine had been developed legally – even democratically,” wrote Kelley,” Once in power, however, it rolled like a juggernaut over the rights of the people.” Kelley was very clear in his observation that the Nazis he interviewed were painfully normal, showing how what happened in Germany could occur anywhere, even the United States: “The Hitlers and the Goerings, the Goebbels’ and all the rest of them were not special types.”

Writing in the late 1940s, Kelley was “convinced that there is little in America today which could prevent the establishment of a Nazi-like state.” Nazi officials were “strong, dominant, aggressive, egocentric” and similar people “can be found anywhere in the country [USA] – behind big desks deciding big affairs as businessmen, politicians, and racketeers.” They had “overwhelming ambition, low ethical standards, a strongly developed nationalism which justified anything done in the name of Germandom.”

While Kelley wasn’t received warmly, people should have remembered the rallies for America First in the 1930s and early 40s, the Nazi rally at Madison Square Garden, the rise of radio preacher and ardent racist Father Charles Coughlin, the renewal of the KKK via the Black Legion, German-American Bund camps that resembled Hitler youth camps. All of this was at the time recent memory.

After World War II, the US War Department pivoted from training and moral-building films to make educational films that helped the public make sense of what happened in Germany. One of them, aptly titled Don’t Be a Sucker, spoke directly about how citizens can be radicalized against “others” and how others follow along until it impacts them directly. The film features an important conversation where a man has his eyes opened by a Hungarian immigrant who saw the Nazis take Berlin. The lesson was that in order to take over a unified country, it must be broken down. The Hungarian man, now a US citizen, said the Nazis “used prejudice as a practical weapon to cripple the nation.”

After Germany was fractured, the “pure” Germans were propped up and boosted as stronger, smarter, and better without any evidence to support superiority. Impressionable people took the bait. “They gambled with other people’s liberty, and of course they lost their own” said the Hungarian immigrant, “A nation of suckers. Hitler needed these people.” Any institution (church, university, union) or group of people that could enact resistance, was attacked and dismantled.

Today, we watch universities threatened and some dismantled, witness skyrocketing xenophobia, and see media institutions bullied into genuflection. In recent weeks, non-violent protesters have been murdered in Minneapolis at the hands of ICE brownshirts. The protestors/observers were labeled domestic terrorists while video evidence countered every official White House talking point. The tide appears to be turning. Many wonder why it needed to get so bad before people woke up.

I’m reminded of a scene from an under-appreciated Civil War (2024), where a group of journalists find themselves getting grilled by an ICE-like citizen-turned-soldier. The journalists say they are Americans but the soldier responds by asking, “What kind of American are you?” Such questions presuppose a dangerous hierarchy that we see increasingly and relentlessly deployed in the United States. A country divided cannot stand, as history has taught us over and over again.

Human nature always runs the risk of falling into authoritarian traps, but, as Rauch pointed out in his column this week, just because Trump is a fascist in nature does not make us a fascist country. Conservatives have been breaking ranks with the King in increasing numbers. We have people and institutions that can serve as a bulwark against bullies. In the coming months and years we’ll see how strong we really are as a nation, if we’re really better than those who came before, or if Douglas Kelley was right, we may never become stronger than Nazi Germany unless “we, as a people, individually develop beyond our present emotional adolescence.”