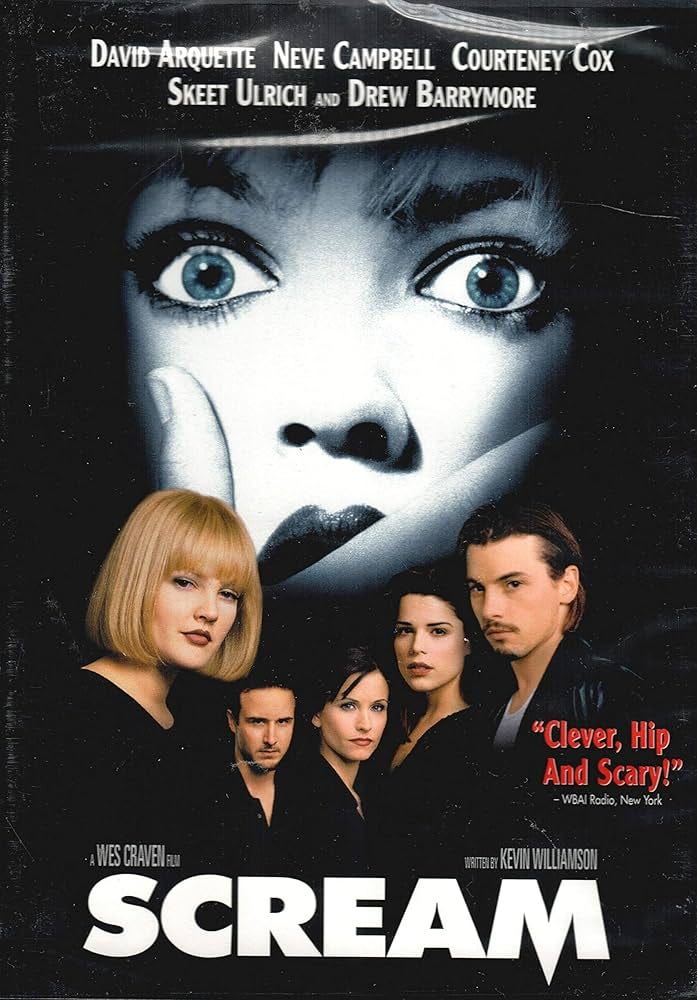

Horror fans of a certain age remember when and where they first saw Scream (1996). The opening scene changed us all forever. Drew Barrymore’s Casey Becker answers the phone, pops some popcorn, and talks movies with a supposed wrong number. The mood is playful until the conversation shifts into terror. Within minutes, she’s dead. The star of the movie, the one on all the posters and advertisements, is gone before the title card.

Scream’s freightening opener is a three-act film in and of itself, observes Ashley Cullins in her knew cultural history of the franchise titled Your Favorite Scary Movie. Cullins summarizes the scenes impact perfects, “it’s at one clever, chilling, and heartbreaking, the kind of unforgettable storytelling that can make something as routine as turning on patio lights at night give you pause decades after watching it.” I remember when Scream came out when I was in middle school. My mom warned me about the film because her friend’s daughters who were high school age babysitters were now afraid to be the only adult home. This, of course, only made me more eager to see the film.

I finally saw the film when it aired on HBO, at which point I was ready with a blank VHS cassette ready to record so I could revisit the film again and again.

The iconic opening scene is familiar to film history fans, because director Wes Craven and writer Kevin Williamson were taking a page right out of Alfred Hitchcock’s playbook. In 1960, Psycho made movie history by killing off its leading lady, Janet Leigh, halfway through the story. Audiences were stunned—she was supposed to be the protagonist, not the first casualty. Scream updates that shock for the ’90s: a hyper-aware generation that thinks it already knows every horror trick in the book.

Craven understood that the rules had changed, having written many of the rules himself. Scream’s teens could quote Halloween and Friday the 13th by heart. So Scream pulled the rug out from a new generation of horror fans—he borrowed Hitchcock’s trick but made it a commentary on the audience itself. When Casey Becker dies, it’s not just a murder; it’s the death of expectation. If Drew Barrymore can’t make it past the first reel, what chance does anyone else have?

Even stylistically, the scene nods to Psycho. The editing tightens as the menace builds. The camera traps us where we feel safe, at home, and turns it into a pressure cooker.

Psycho shocked viewers who thought Hollywood stars were untouchable. Scream shocked viewers who thought being in on the joke would keep them safe. Both are reminders that horror, at its best, punishes complacency.

The famous shower scene

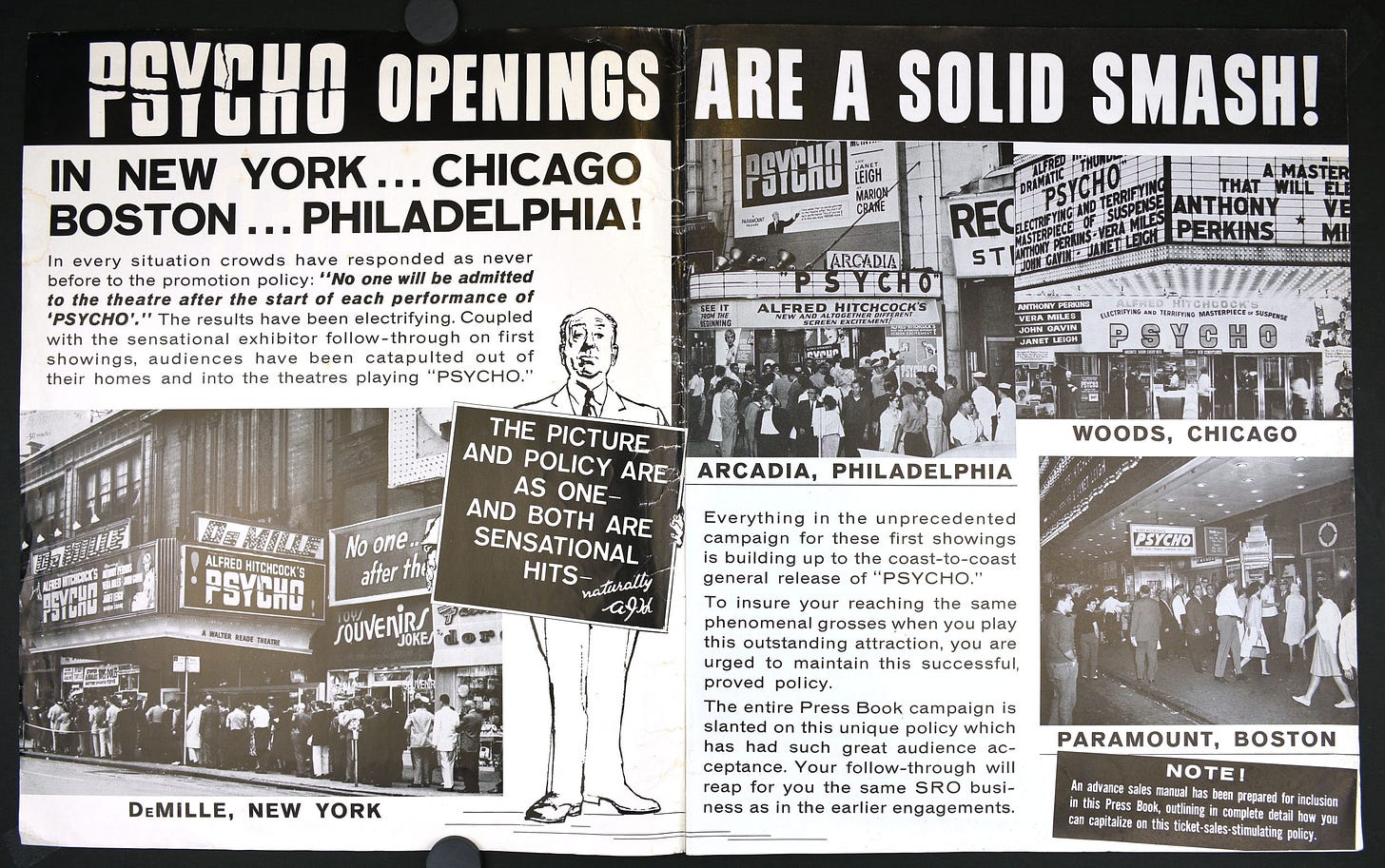

Hitchcock’s pressbook with directions on proper exhibition. The maestro knew he was going to floor audiences, so he made sure nobody came into the film late. This way, the blow of losing the film’s star would be felt in full. Word of mouth spread like wildfire and long lines developed at theaters across the country.

Watching Psycho today, the infamous shower scene remains terrifying. The film lulls the viewer into complacency, setting up every expectation that the main character will prevail, until the bathroom door opens.

The lesson is that great horror keeps us guessing. Jump scares fade quickly, but emotional manipulation hangs on forever.

Paramount’s “visual pressbook” on Psycho from 1960